If the

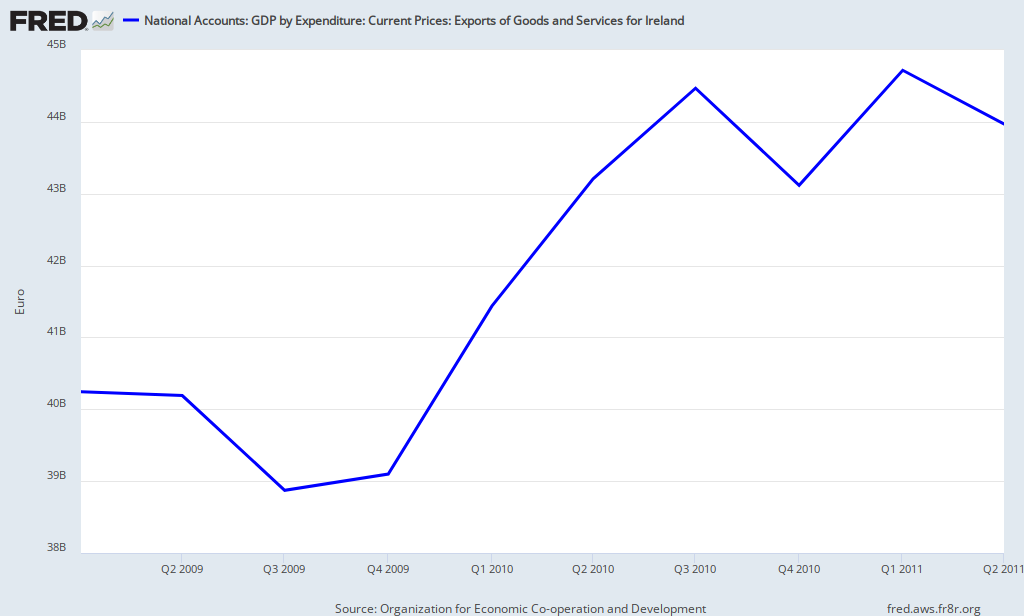

The lack of significant recovery and the impact of wrong headed austerity in Ireland

In a country where the rate of non payment of debts and home repossession has traditionally been very low, weekly repossession cases like these have become a potent symbol of the property boom and bust that last autumn catapulted

The situation is getting worse, not better

An official report this week highlighted a “dramatic rise” in mortgage arrears, warning that the trend would continue owing to government budget cuts, which are continuing to bite under the terms of the country’s EU-IMF rescue programme. At the end of June, some 56,000 mortgages were in arrears of more than 90 days, around 7 per cent of homeowners. A further 70,000 accounts have already been restructured by lenders because families ran into financial difficulties.

But while in the U. S. banks are proceeding en masse to foreclose and evict, even ignoring the legal niceties of doing so, in Ireland

Despite the rapid growth in mortgage arrears, repossession rates remain low, with fewer than 1,000 since September 2009 – partly because prices have fallen so far that the banks cannot recoup their losses.

“There is no market for banks to sell houses at the moment, and it is better for them to have houses occupied rather than lying vacant and losing value. But all the time the level of arrears is growing,” says David Duffy, economist with the Economic and Social Research Institute.

See, that is a rational economic temporary solution, but banks and lenders in the United States are rarely rational, so they are evicting homeowners and taking over the property themselves, thus having to pay to maintain the housing while at the same time driving down the price of housing, making the situation even worse for themselves.

This kind of thinking (or lack thereof) sort of explains how they got in trouble in first place. Certainly thinking was neither part of the creation of the problem nor part of the solution.

DPE. I'm told that U.S. banks can write off the remaining amount owed on a repossessed house (amount of mortgage minus payments made)which is why the banks don't care about resale value per se or how long resale takes. If true, that sounds like a real tax impetus for banks to take a house that has an underwater mortgage ASAP--ultimately at the expense of U.S. taxpayers.

ReplyDelete